North Carolina is grappling with a significant shortage of teachers, leading to heavy reliance on substitute educators to fill essential roles in K-12 schools. To combat this issue, there’s a push to increase enrollment in education programs at the state’s colleges and universities. One proposed solution, put forward by the North Carolina Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (NCACTE), suggests removing the Praxis core exams as a requirement for enrolling in educator preparation programs (EPPs). Additionally, they advocate eliminating licensure exams for graduates of these programs, arguing that these assessments serve as barriers to placing more diverse teachers in classrooms.

The rationale behind NCACTE’s proposal centers on concerns that standardized tests create inequities, particularly for diverse candidates. They argue that these exams do not accurately assess readiness or predict success in teaching roles. Instead, they propose focusing on alternative assessments like the edTPA and PPAT, which are seen as more comprehensive and reflective of candidates’ abilities over time.

However, critics contend that eliminating standardized exams could compromise the quality and rigor of teacher preparation. They argue that these exams provide objective measures of competency and preparedness, essential for ensuring that teachers are adequately equipped to meet the demands of the classroom.

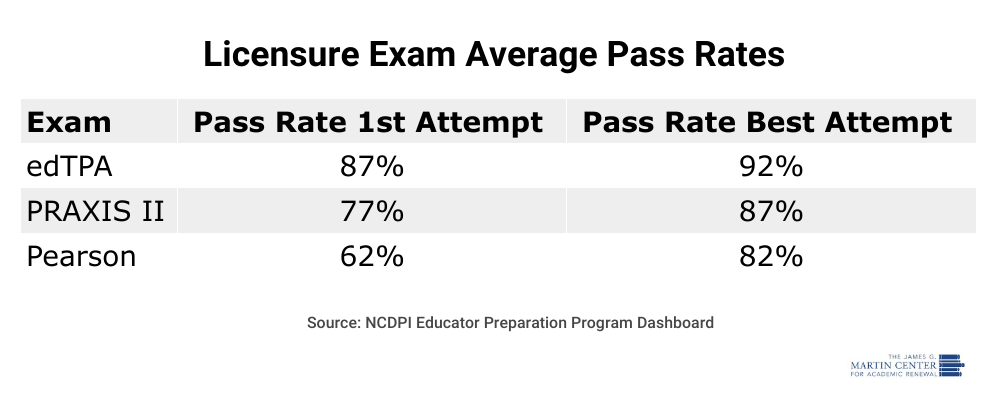

Data from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s Educator Preparation Program Dashboard reveals varying performance outcomes across different assessment types. For instance, the edTPA has shown high pass rates among candidates, suggesting success with portfolio-based evaluations. In contrast, the Praxis II exams, known for their standardized approach, have slightly lower pass rates but are viewed as critical for assessing content knowledge and pedagogical skills in a more objective manner.

The debate underscores broader questions about the role of standardized testing in teacher licensure and educational equity. Proponents of maintaining these exams argue that they uphold rigorous standards and ensure consistency in teacher quality. Conversely, advocates for reform argue that alternative assessments could better capture the complexities of teaching readiness, particularly in diverse and underrepresented populations.

Ultimately, the path forward for North Carolina involves balancing these perspectives to strengthen its teacher pipeline while maintaining high standards of educator preparation. The outcome will likely shape not only how teachers are trained in the state but also the diversity and effectiveness of its educational workforce.

If anything, student underperformance on the more objective measures of learning suggests that some teacher candidates have not been well-prepared by their college education programs. This points directly at the quality of education being achieved at North Carolina’s EPPs.

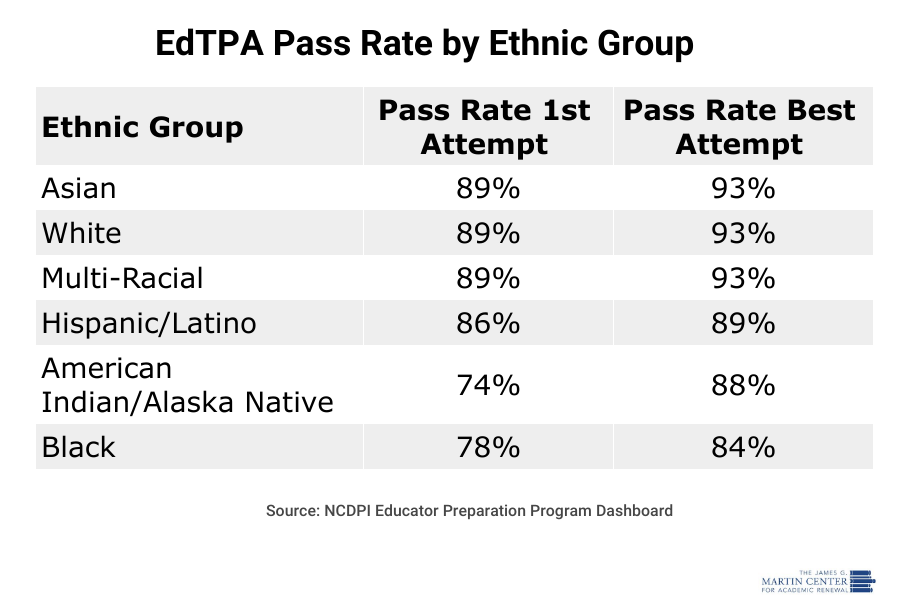

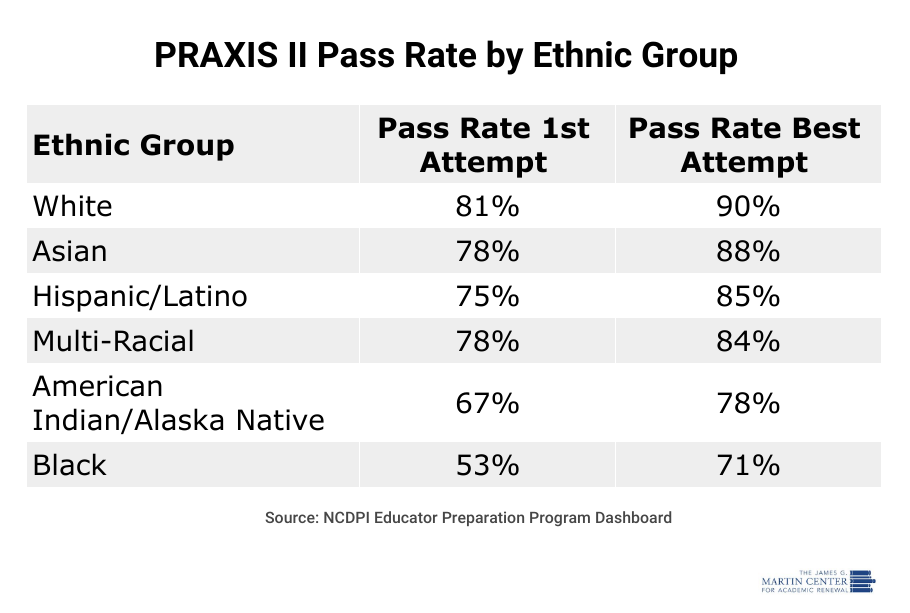

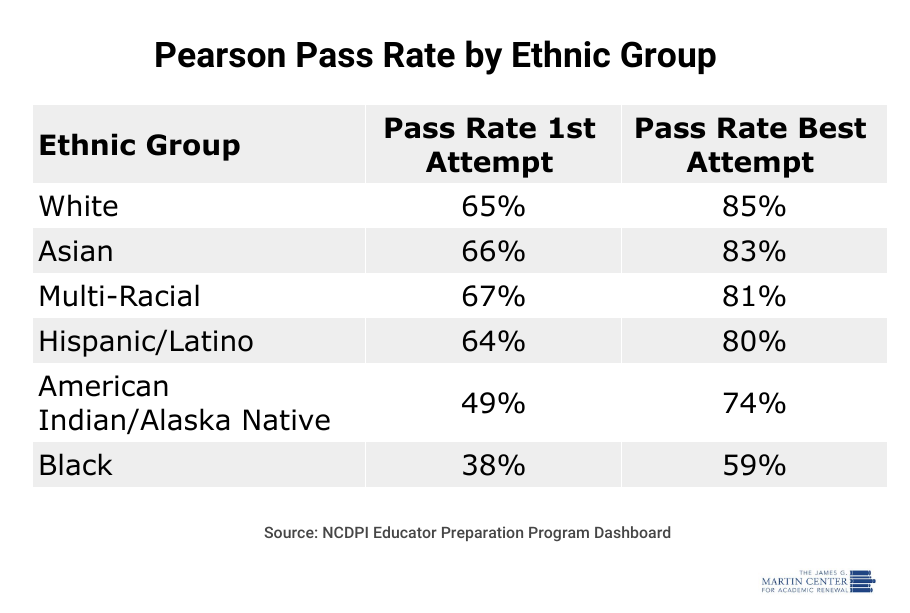

Yet, as previously mentioned, NCACTE’s proposal to do away with standardized testing for teacher candidates is not only about overall student performance. Rather, it is about “diversity.” When one disaggregates the score data for each exam on the basis of race/ethnicity, it becomes clear that a few groups have fallen behind in pass-rates. Both Pearson and PRAXIS II data show that American Indian/Alaska Native and black candidates have lower passing rates on their first and best attempts than do other ethnic groups. Meanwhile, Asian and white candidates top the board on each exam type.

As these data show, the tests in question do appear to have a “disparate impact” on some minority students. Nevertheless, the exams are nowhere near insurmountable enough to justify their elimination. Yes, some people struggle more than others, but that could be the result of many factors (for example, program-student “mismatch”), thereby making it illogical to simply blame the exams.

Let’s not forget, too, that candidates get three years to take and pass these exams. And as the dashboard makes clear, 84 percent of the candidates who pass the exams pass them on their first attempt. The success percentage increases for every subsequent exam attempt.

Standardized exams are effective in part because of the barrier they create. By putting in the effort that it takes to pass such exams, students prove their knowledge. If they fail, then the barrier to entry remains, separating those who are determined to push through to success from those who are not.

NCACTE has argued publicly that North Carolina should maintain high “standards for teacher preparation” in order to ensure that teachers are well prepared for the classroom. The irony is palpable. In the same breath that NCACTE expresses concern about producing high-quality teachers and maintaining high standards, it argues for taking away perhaps the most useful tool for determining if teacher candidates are prepared for the responsibility of teaching in the classroom. It’s difficult to understand how these two sentiments can coexist.

Without standardized tests, North Carolina’s teacher-licensure process would rely exclusively on EPPs to prepare and test teacher candidates. But why rely on one preparation method when you can boost candidates’ chances of success by implementing multiple tools to test their knowledge?

The Martin Center has often made a similar argument in support of the use of SAT/ACT scores and GPA in college admissions: Two methods are better than one. Standardized tests are likely even more necessary in this case, however, as teacher-education candidates will ultimately be teaching younger generations.

The Martin Center has attempted to contact NCACTE to learn the current status of their recommendations; however, the organization didn’t provide a quote in time for publication. At this time, it doesn’t appear that the recommendations in question have gained much or any traction. While this is currently to the benefit of future N.C. teachers and K-12 students, it doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods.

Indeed, it’s becoming increasingly popular to advocate for the lowering of standards at colleges and universities under the guise of increasing diversity and inclusion. But it’s important to acknowledge that these standards were implemented for a reason. Parents want the best quality education for their children, whether in K-12 or higher ed. Let’s not be fooled into believing that that can be achieved by eliminating all barriers to entry.