In the realm of legal education, the debate over racial preferences in admissions has been a contentious issue for decades. Professor Richard Sander’s seminal work, particularly his research on the “mismatch” effect in law schools, has significantly shaped this discourse. This essay delves into the implications of Sander’s findings, the responses they elicited, and the ongoing implications for legal education and diversity initiatives.

The Origins and Findings of Sander’s Research

In 2006, Richard Sander published groundbreaking research in the Stanford Law Review, highlighting significant disparities in academic outcomes between Black and white law students attributable to racial preferences in admissions. Sander’s research indicated that, contrary to their intended purpose, these preferences often placed Black students in academic environments where they struggled to perform at the same level as their peers. Key findings included:

- Academic Performance: Black students admitted with substantial preferences had undergraduate grades and LSAT scores significantly lower than their white counterparts at the same law schools.

- Graduation and Bar Passage Rates: Black students were more likely to fail out of law school, graduate with lower grades, and struggle to pass the bar exam compared to their white counterparts.

- Mismatch Effect: Sander argued that eliminating racial preferences would actually increase the number of successful Black lawyers by placing them in schools where their academic credentials matched the institution’s academic rigor, thereby improving their chances of academic success.

Response and Critiques

Sander’s research sparked widespread attention and debate, both within academic circles and in national media. While many scholars acknowledged the importance of addressing racial disparities in legal education, critiques of Sander’s findings focused on methodological limitations and the complexity of attributing causality solely to mismatch effects. Some key critiques included:

- Circumstantial Evidence: Critics argued that Sander’s evidence was largely circumstantial due to limitations in data availability and the inability to measure individual student outcomes directly across different types of law schools.

- Alternative Explanations: Alternative explanations, such as institutional climate or stereotype threats faced by minority students, were proposed as potential factors contributing to disparities in academic outcomes.

- Data Accessibility: Challenges in accessing comprehensive data on law school admissions and outcomes hindered efforts to independently verify or refute Sander’s findings across a broader range of institutions.

Despite these critiques, Sander’s work catalyzed a broader discussion on the unintended consequences of racial preferences in admissions and the need for transparent data to inform policy and practice in legal education.

Recent Developments and Policy Implications

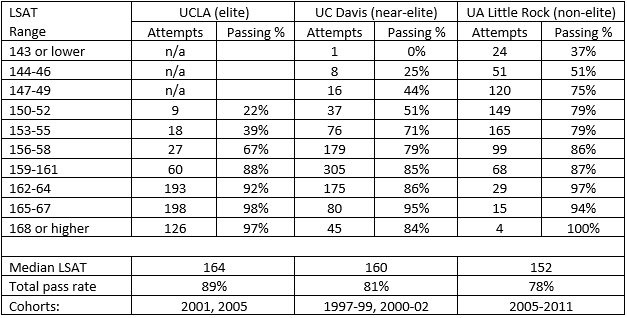

In recent years, Sander and his colleagues, including Robert Steinbuch, have continued to advocate for transparency and data-driven approaches to evaluating the impact of racial preferences in law school admissions. Their efforts to secure the release of comprehensive data sets from multiple law schools have provided further insights into the correlation between mismatch and academic outcomes.

Recent findings indicate that mismatch remains a significant predictor of bar exam passage rates, particularly among Black and Hispanic students. The data suggest that reducing mismatch could substantially narrow racial disparities in legal education outcomes, challenging assumptions about the necessity and efficacy of large preferences.

Supreme Court Cases and Future Directions

As the Supreme Court prepares to rule on cases challenging the legality of racial preferences in admissions at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, Sander’s research assumes renewed significance. Many anticipate that the Court may curtail the use of racial preferences, prompting universities to reconsider their admissions policies.

Potential outcomes include a shift towards more subjective criteria in admissions evaluations, such as personal essays, to circumvent legal restrictions on race-based preferences. Alternatively, some institutions may defy legal rulings and continue to prioritize diversity initiatives over strict adherence to merit-based admissions criteria.

Conclusion: Implications for Legal Education

Richard Sander’s research on the mismatch effect in law school admissions has profoundly influenced discussions on diversity, meritocracy, and educational equity in legal education. While contentious, his findings underscore the importance of balancing diversity goals with academic preparedness to ensure equitable opportunities for all students.

Looking forward, the integration of rigorous, transparent data analysis into admissions policies could provide a path forward towards addressing racial disparities without compromising academic standards. By fostering open dialogue and evidence-based decision-making, legal education institutions can navigate the complex terrain of diversity initiatives while upholding principles of fairness and meritocracy.

In summary, Sander’s work continues to provoke reflection and debate, challenging stakeholders to reconsider long-standing assumptions about the role of race in admissions and its impact on educational outcomes in law schools and beyond.